Are You a Follower, a Bender, or a Breaker?

Rules are meant to be [FILL IN THE BLANK]

BEACH CLOSED, said the sign. HAZARDOUS.

And yet the people walked toward the sea.

When my boys were in elementary school, their principal sent out a weekly email containing parenting tips and anecdotes. In one such message, she told the story of a mother and child she’d seen at the natural grocery. The child reached for something marked off-limits. The principal overheard the mother say, We’re not supposed to touch those, but let’s do it anyway.

I hope that child doesn’t go to my school, our principal wrote. I’m a rule follower.

The rules keep us all safe, she went on to explain. They keep our community running smoothly.

Of all the emails I received from her during our years at that school, this is the only one I remember.

I was raised to be a rule challenger, bender, and, in some cases, breaker. I was a young child when Timothy Leary popularized the phrase Question authority, but its guiding principle was baked into my DNA. My parents were anti-war and civil rights activists. I marched against the Vietnam War when I was three years old. My dad was a leader in a movement to integrate the swimming pool in my hometown of Lawrence, Kansas, a movement that eventually led to the creation of a public pool that all could enjoy. My mom, though reserved and soft-spoken, wore jeans in college as part of a coordinated effort to overturn the college’s dress code for women. She marched on civil rights picket lines. Much later, as a faculty member in the statistics department at UC Berkeley, she mentored women in math and science and pushed back against attempts to favor American PhD candidates over more qualified international students.

Of course these are very different kinds of rules from the ones my boys’ school principal was talking about. These were matters of principle, not safety or courtesy.

Even so, when I read the words, I’m a rule follower, my gut registered it as if she’d written, I’m a sheep.

Yet though I would never say, I’m a rule follower, I would also never say, The rules don’t apply to me.

The former calls to my mind the sickening phrase just following orders—also known as the Nuremberg defense—while the latter evokes a certain orange braggart who deems himself above the law.

So what’s the difference between a rule breaker and one who thinks the rules don’t apply to them?

From my perspective, the first seems to challenge the validity of the rules themselves, while the second says, “those rules are fine for others, just not for me.” Rebelliousness versus elitism.

In art and science, as well as activism, it’s always the rule breakers—the ones who refuse to accept conventional wisdom at face value—who move humanity forward. Think of Copernicus, bucking church doctrine with his model of a sun-centered universe. Of Cervantes, breaking the fourth wall to create a new kind of novel. Of Georgia O’Keeffe, shaking up the male-dominated art world with her unique blend of representation and abstraction.

But maybe I’m just making excuses.

Not me, not my dog.

A friend of mine recently took an online quiz that asked if she identified as a rule follower. She checked yes. It then asked whether she ever exceeded the speed limit, jaywalked, or rolled through a stop sign. Umm… Her answers to those follow-up questions caused her to rethink her answer to question number one.

Principled action aside, my boundary-pushing behavior these days is along the lines of moving to a better theatre seat at intermission or taking my dogs someplace they’re not supposed to go. My compass for evaluating such things is to ask myself whether my actions are hurting anyone. If the answer is no, I’m likely to proceed, perhaps with a shred of guilt (Is the “no dogs” rule intended to protect wildlife? But surely if I keep them on leash and pick up their poop…).

The term cognitive dissonance refers to the way our brains freak out when faced with contradictions. Many studies have shown that when we behave in ways that contradict our core values, our minds perform all kinds of contortions to justify our actions. I’m an honest person, but I had to tell this lie because of the all-important x, y, or z.

My dad was among the most honest people I’ve ever known. I don’t recall him ever telling a lie. But he was always willing to bend the rules for my sake.

Forty years ago, while attending Lawrence High School in Lawrence, Kansas, I took voice and acting classes at the University of Kansas. Officially, this made me a KU student, so I was able to audition for shows in the Department of Theatre and Dance. This led to me being cast as Fredrika in Sondheim’s A Little Night Music on the KU mainstage during my junior year of high school.

Someone must have complained about this, because the next year—my senior year of high school—the university made a rule that you had to be enrolled in a certain number of academic hours to be eligible to perform in department shows.

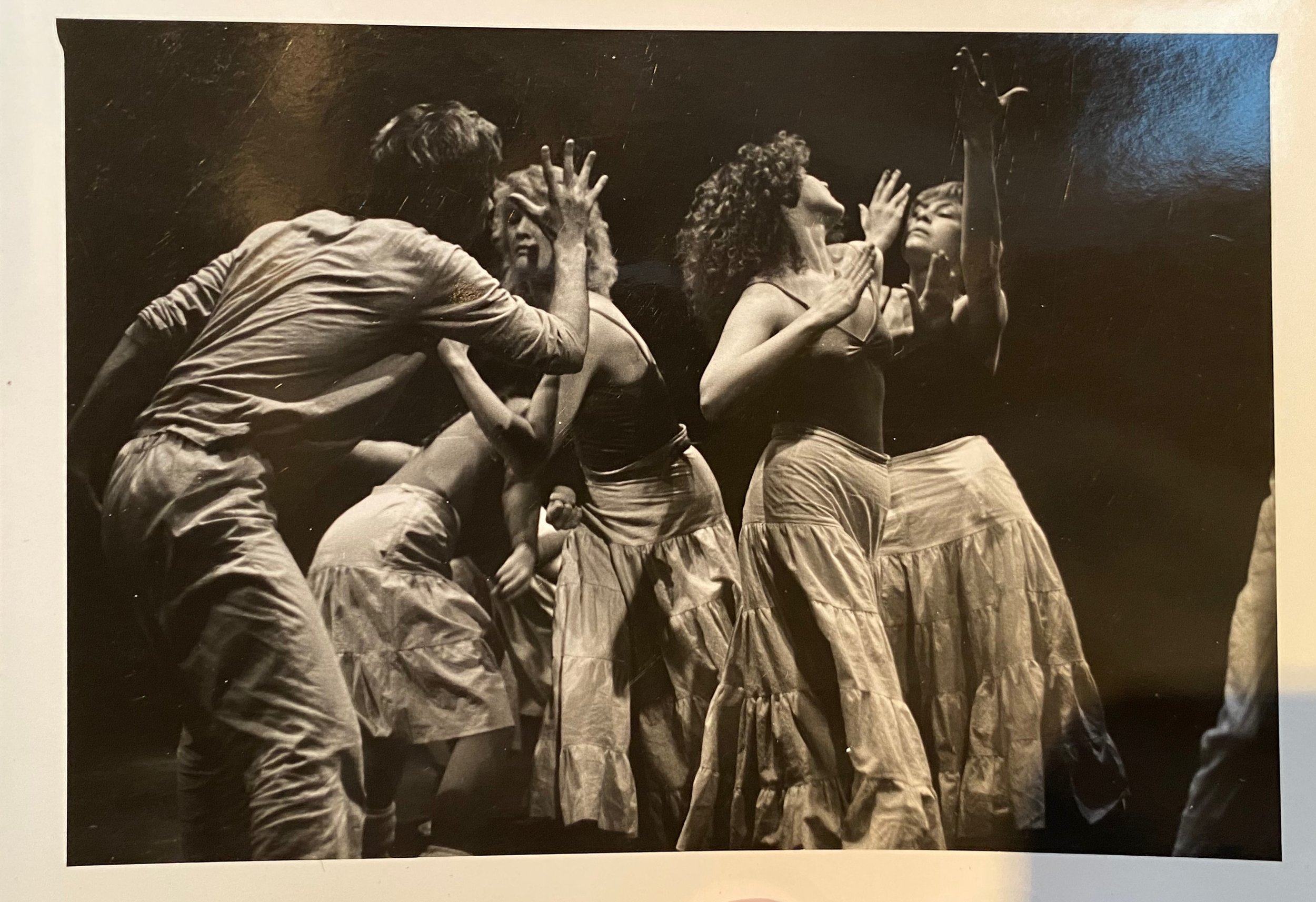

That semester there was a production called The Oedipus Project that I was desperate to be a part of. The director, Dr. Robert Findlay, had worked with the legendary Polish experimental theatre director Jerzy Grotowski. The Oedipus Project was to be a five-month journey in which the cast, under Bob’s direction, would collectively create a performance based on the Oedipus myth.

I wasn’t enrolled in the full-time class schedule the new rule required. My dad and I put our heads together and came up with a plan to enable me to audition: we’d register me for the requisite number of hours and drop some of the classes once casting was complete. It worked, and I was cast.

The Oedipus Project changed my life. We developed the piece through daily “paratheatrical events”—ritualistic multi-hour sound and movement improvs. During those rehearsals, I entered a kind of altered state, in which I learned to get my brain out of the way and think with my body, allowing myself to be absorbed in the collective motion and rhythm of the group. I learned things about the creative impulse that continue to impact my work to this day. The director, Bob Findlay, became a long-time friend and mentor.

Looking back all these years later, I see my dad’s and my action as at best morally gray and at worst profoundly self-serving at the expense of other students, some of whom may have come to KU specifically for opportunities such as this.

Yet though I feel guilty sharing this story, I’d be lying if I said I regret it.

I’m a Libra. I’m always spinning the prism round and round, looking at things from different angles. On the one hand, by scoring that role, I may have deprived another student of a life-changing experience. On the other hand, to another student The Oedipus Project might have been just another show.

And though I fudged my enrollment status to get in the door, I won the role through an open audition process, in which I had the opportunity to communicate my passion for the project as well as my skills.

As a young actor, many people in positions of power told me that to do this thing, you had to want it more than anything in the world. During a college semester spent studying acting in London, one of my teachers told a story about an actor putting a headshot under a casting director’s door every day for eight months in an attempt to land an audition for a particular role. This actor didn’t have the right agent or the right resumé, but she had the grit. She got her audition, and she got the part. This was framed as an inspirational tale. The message? Do whatever it takes.

This makes me wonder—does how much you want something change your relationship to the rules? Should it? Should rules bend to accommodate overriding passion? Is all fair in love and art? Or is that just another excuse?

Let’s not burn it all down.

We Americans love our renegades, our mavericks, even our outlaws. After all, we’re a nation born of revolution. Even as we acknowledge the painful truth that we’re also a nation born of mass bloodshed and bondage, most Americans still cherish the iconoclastic, freethinking aspect of our national character.

Questioning unjust rules is the positive side of this American coin. Taking what we want for ourselves and our families and everyone else be damned is the negative side—one that’s leading us down a path of humanitarian and environmental disaster. I hope as a nation we can melt that coin down and refashion it in a way that combines the righteous impulse to question authority with true caring for the safety and well-being of the community before it’s too late.

The sign I photographed on Carmel Beach on December 30, 2023, had originally read, BEACH CLOSED. HAZARDOUS CONDITIONS. Over the previous two days, towns along California’s central coast had been evacuated and at least eight people hospitalized as 30-foot waves pounded the shores.

On that day, someone had covered the word CONDITIONS with silver paint and drawn a slim line through the center of the word HAZARDOUS. Who covered it, I wondered, and what did it mean? Were the conditions now only semi-hazardous?

Sitting in my Michigan living room as the snow piles up outside, I search online for information about the conditions on Carmel Beach that day. It seems the wave size had diminished somewhat that afternoon, and the warning had been downgraded to an advisory. Semi-hazardous indeed.

Did the people on the beach know the warning had been downgraded? I certainly did not. I’m guessing a few did, and the rest, witnessing others passing the yellow caution tape without apparent consequence, followed suit. That’s another thing about us humans. We’re a lot more likely to break rules if we see others doing it. For better or for worse.

As I watched a man play catch with his son, the child standing below the tide line, and others throwing balls into the surf for their dogs to retrieve, my judgmental brain clamored in my ear, How can they put their children and dogs at risk that way?

And yet, how beautiful the ocean looked, how soft the sand.

And so I stood with my son halfway down the dune, past the yellow caution tape but well above the beach, my Libra self ambivalent as always, trying to have it both ways.

Carmel Beach, December 30, 2023

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear,” wrote Joan Didion. If you feel called to explore your life in words, I invite you to join my Off-Leash Writing Workshops or Memoir, Fiction, & Personal Essay Workshops. I also work with people privately on their writing and editing needs. Email tanya@offleashwriting.com to inquire.