The Exuberant Professor: Introducing Harry

Dear Friends,

For years I’ve been planning to write a book about my extraordinary dad, who survived displacement and incalculable loss and yet remained the sunniest, most open-hearted person I ever knew. My previous book Somebody’s Heart is Burning, about my travels in West Africa, grew out of more than a dozen individual stories I wrote for Salon.com’s now-defunct Wanderlust section. It occurred to me recently that I could develop this new book in the same way—that instead of waiting until I have an entire manuscript, I can share these stories with you as they arise.

I therefore invite you to meet Harry G. Shaffer, the exuberant professor.

THE EXUBERANT PROFESSOR

Introducing Harry

There he is—Professor Harry G. Shaffer. See him tearing around the campus of the University of Kansas like a man hellbent on jotting down an idea before he forgets it. See his white hair flying, papers spilling from his old-style leather briefcase, his jacket and suspenders and lightly scuffed Florsheim shoes. See him adjusting the microphone for his intro economics class, where he lectures to some 300 students at a time in his scratchy, heavily accented voice. See how these students adore him, how they laugh at his jokes, repurpose his sayings, draw hearts on their end-of-term evaluations and write comments like, “I want to sit him down by the fire and feed him warm cookies” and “I wish he were my Grandpa!” Behold the Facebook group Harry Shaffer is the Man, made up of current and formers students, which at the time of his death in 2009 boasted 800+ members. Read tribute after tribute to “the man who never left home without his toothbrush.” See how they celebrate his daily greeting, “Good afternoon!,” sometimes transcribed phonetically as “Gut ahftanun!”

His students called him Professor Shaffer. I called him Vati, pronounced FAH-tee—German for daddy.

My Vati loved his students. Even after 54 years of teaching, he particularly relished that gigantic undergraduate intro class. He was a performer—he liked a big stage. He enjoyed turning young adults on to the fun of economics, bucking their assumptions that it would be dry or boring. He demanded their attention, pausing abruptly and saying, “We will wait,” if anyone engaged in side chatter. He taught them the origins of money through a story involving bartering and fish hooks, and how the difficulty of carrying fish hooks in your pocket without cutting yourself led to the development of coins.

Harry made sure his students understood the difference between political systems and economic ones. He disabused them of the notion that socialism and democracy were incompatible. An unapologetic Marxist, his proudest moments came when he received letters from former students telling him he’d changed their career trajectories and, thanks to his teaching, they’d decided to dedicate their work lives to social justice rather than profit.

My dad reveled in his local fame. He loved when students came up to him and told him they’d taken his class, or that their father or mother had taken it. He crowed with delight when he called me to tell me that, for the first time, a student had come up to tell him their grandfather had taken it.

He found that story hilarious. It reminded me of other tales he gleefully related, of people asking whether my mother was his daughter. “Only once,” he said, “did someone ask me if she was my granddaughter!”

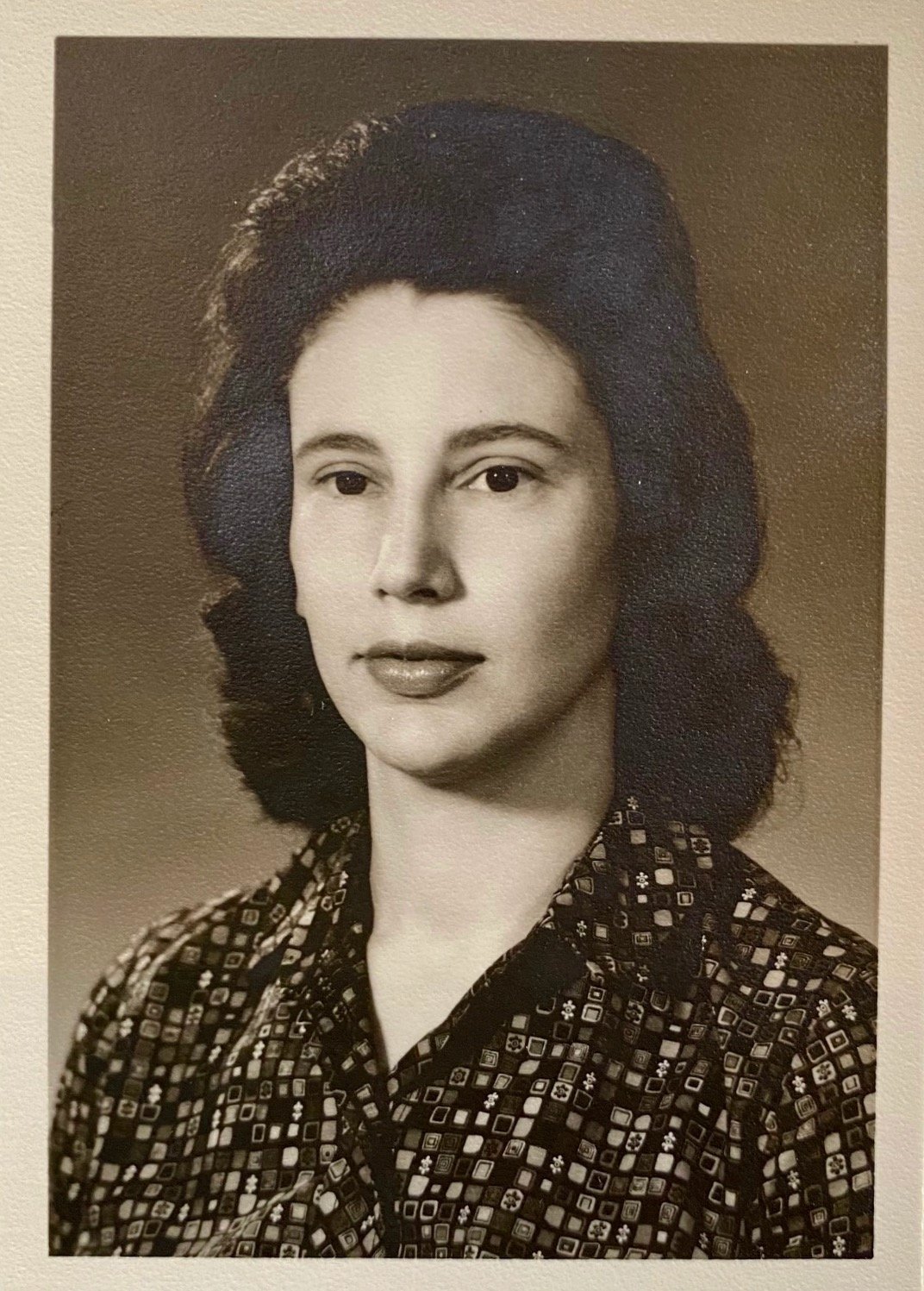

My dad was fourteen years older than my mom, Juliet Popper Shaffer, but with his thick glasses, receding hairline and early gray, he looked old for his age, while my mother looked young for hers. They were both professors at KU when they met through the Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy, a group dedicated to combating racism in my hometown of Lawrence, Kansas. My dad was immediately smitten with the raven-haired beauty who listened so attentively to the debates. She rarely spoke at meetings, but according to my dad, when she did, everyone in the room held their breath and leaned forward to catch every word. Her remarks were pithy and incisive, succinctly synthesizing complex ideas, putting the bloviating men to shame. He always thought she was too good for him—too beautiful, too smart. He was perpetually afraid she would leave him. Eventually, she did.

Harry George Shaffer was born Hans Georg Schaffer in Vienna, Austria, in 1919. When he immigrated to the United States in 1940, he tried to excise every whiff of German-ness from his name. He even dropped the “c” from his surname, little knowing he was dooming his children to a lifetime of repeating “Shaffer, no ‘c’.”

As a child, he had a mass of curly white-blond hair. One of his nicknames was Flocki—little cloud. His parents divorced when he was a toddler. As unusual as it was in Kansas for my parents to separate when I was seven, it was even more unusual in 1920’s Vienna.

A few years later, my dad’s mother remarried. Her new husband did not want the burden of a young child, so Hansi was sent to live with his mother’s parents, his Oma Rosa and Opa David. They were Orthodox Jews—my father recalled his grandfather binding the tefillin every morning, affixing the little black box containing Hebrew scrolls to his forehead and crossing the cords on his arm before he prayed.

Many years later in New York City, my Vati’s Grandma Rosa—having lost two of her three children, one to the camps and one to cancer—would put her head in an oven and end her own life. But we’re not there yet. We’re talking about my dad’s childhood, which despite his parents’ divorce and his relocation to his grandparents’ home, he remembered as a happy time.

I’m named for my dad’s mother Teofilia, who went by the nickname Tosca. We Ashkenazi Jews are liberal in our naming conventions—to honor an ancestor, only the first letter has to be shared. That, and they have to be dead. I could not have been named after Tosca if she had lived to see my birth. She made it out of Austria and all the way to New York, where she ran a bridge club, but cancer took her, far too young.

My father adored his mother. He told me she visited often, perhaps two or three times a week, and he looked forward to her visits with unbridled delight.

Photos of Tosca show a strikingly beautiful woman with an hourglass figure, softly curling golden hair and a gentle, flirtatious smile. She looks like a movie star in her stylish hats and satin flapper gowns. I imagine that tiny tow-headed boy flinging himself into his mother’s arms every time she opened the door. I imagine her soft cheek pressed to his, her kisses leaving lipstick impressions all over his face as he squeals with delight, her smell of powder and perfume. For surely she was affectionate like this, or how could my dad have become the huge-hearted person he was?

If my Vati felt any resentment towards his mother for submitting to her husband’s demand to live separately from her child, he never expressed it. Neither do I judge, for who knows what options were available to a divorced woman in 1920s Vienna? Years later, my dad would make a similar choice involving my mom and one of my older brothers, who was fourteen at the time—a choice he would rehash with sorrow and guilt for the rest of his life. But that too is a story for another time.

He always told me Tosca would have been crazy about me. I’m sure I would have been crazy about her too.

Can you see him, the ninety-year-old man that little Flocki grew into, the one who was still teaching economics at the University of Kansas six months before he died?

Of course, there was a world of experiences in between. So many losses: his home; his country; his beloved uncle to the camps; his mother to cancer; his grandmother to suicide; his beloved first wife to a surgery gone wrong; his second wife, a fellow survivor, to mental illness; his third wife—my mother—to another man. There was exile in Italy, then Cuba, on the way to the U.S. There was his time in the U.S. military during World War II, cut short by a jeep accident that left him with multiple broken bones. His education at NYU, where in four years under the GI Bill he managed to complete his bachelor’s, master’s, and two courses towards his PhD. There was his first teaching job at the University of Alabama, where he was one of a group of faculty members who resigned over the university’s failure to protect Autherine Lucy, the first Black woman admitted to the university following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. There was his activism in the anti-war and civil rights movements. There was his happy fourth marriage to my stepmother Betty, with whom he spent the last 25 years of his life. And there was the role he valued most, as father to his four children from his first three marriages, a role he often carried out on his own.

And of course, this is only a tiny fraction of a life’s journey. There’s so much more to tell.

I was with my Vati in Lawrence on his ninetieth birthday. At some point during that visit, he sat beside me on the light brown velvet couch in the living room of the two-story house I grew up in and said to me, in his still-strong Austrian accent, his voice roughened by years of repeated surgery on his vocal cords for nodes that just kept growing back, “Pippi, if I should die, I want you to know I’ve had a good a life, and one of the greatest joys of my life was raising you.” Pippi was one of his nicknames for me. It evolved out of the German word Puppe, meaning doll.

My dad had struggled with asthma throughout his life. For the past two years he’d been wheeling around an oxygen tank to assist his weakening lungs. But because I’m a doofus, and because we live in a culture that steadfastly refuses to acknowledge mortality, I replied, “C’mon, Vati, you’re not going to die!”

Yes, that’s how I responded when my father told me, in so many words, that he was getting ready for what came next. I refused to listen, but I heard.

Two months later, he was gone.

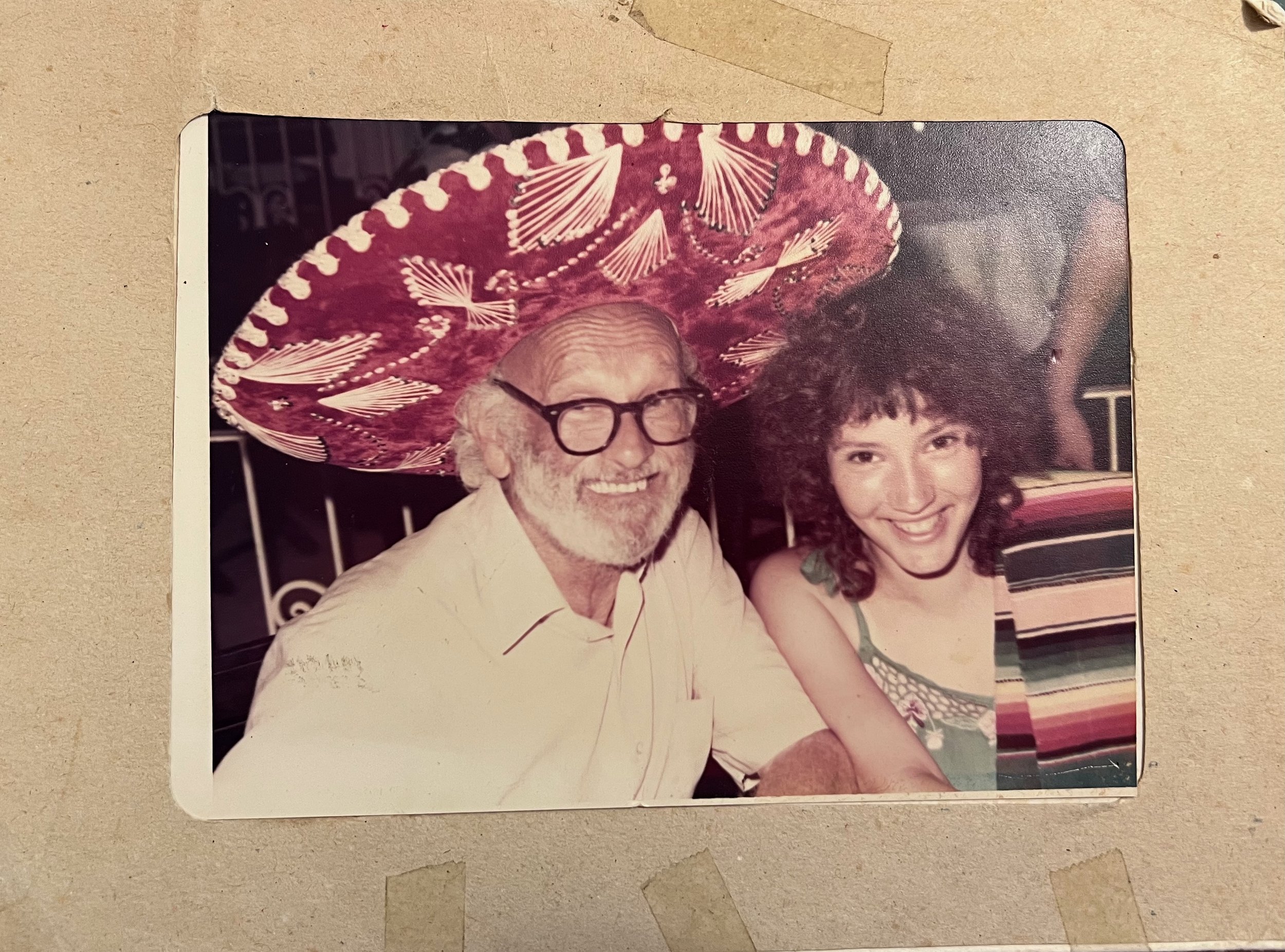

Vati and me in Puerto Vallarta, celebrating my high school graduation

For as long as I could remember, I’d feared my father’s death. If you look at my diaries, which I kept daily from the time I was nine years old, every day’s entry ends with repeated prayers for my Vati to live a “very very very infinity very long time.” He was substantially older than all the other dads, he spent half of every year coughing, and he was always going into the hospital for surgeries while I stayed at the homes of various friends. On top of that, he was a bit of a hypochondriac. A year after my mom left, my youngest brother went to live with her. My two oldest brothers were already living independently, so my Vati and I became an inseparable duo for many years. It’s no wonder I was constantly pleading with the powers that be for his survival.

I was sitting on the floor of my older son’s room, in El Cerrito, California, building towers out of cardboard bricks, when I got the call. My younger son, just one year old at the time, was strapped to my body in a sling while my older guy stood to add another block to our teetering creation. My husband was typing at his computer in the next room. Moments before the phone rang, a thought had come to me. I’d thought, “I’m settled now. I have my own family. If I were to lose my Vati, I would survive it. I’d be okay.”

While I was having that thought, my father and his beloved wife of 25 years, my stepmother Betty, had returned from shopping and were climbing the back stairs to the kitchen in the house I’d grown up in. Halfway up the stairs, my Vati had to sit down and rest, because he was out of breath. Betty sat on the step beside him.

“Betty,” he said, “I don’t want to do this anymore.”

“Harry, you don’t have to do anything you don’t want to,” said she.

My Vati sighed, leaned into the arms of his beloved, and lost consciousness. A moment later Betty was panicking, shouting, calling 911. An ambulance came, but my Vati never regained consciousness.

Betty told me later that was the first time she’d given him permission like that. At other times when he’d tired of the effort of pulling in air, she’d encouraged him to buck up, telling him that once he’d rested he would feel better.

Betty and my father had been deeply in love for 25 years. Like me, she was terrified of losing him. It was an enormous comfort to her that he went so peacefully, without pain, without fear. Though she missed him awfully, the ease of his passage helped to soften her own transition to life on her own.

Fourteen years later, I still think of him every day. Even now, there are moments when I can’t believe I’m living in a world without his light. But then I wonder…am I truly without him, if I’m still warmed by his love after all these years?

My father believed in God. My mother emphatically does not. All my life I’ve struggled to stay open to the possibility that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy (to paraphrase Hamlet), in the face of deeply ingrained skepticism inherited from my mom. I will never know whether the thought that came to me—his youngest child and only daughter—on November 3, 2009, somehow reached my Vati and joined forces with Betty’s permission to help release him from his earthly bonds.

I remember sitting with him on that same tan couch a few years before he died, telling him about the Buddhist notion of nirvana: that when you become enlightened, you’re freed from the pain of individuality and absorbed, finally, into a oneness with all beings. At that point I’d been studying Buddhism for twenty-plus years.

I remember the way he looked at me, his gray-green eyes aglow with hope, when I said, “If we get there, we’ll never be separated again.”

Vati holding me in Munich around 1967

With my parents and my brother Len in Munich

With all three of my brothers and Betty’s two kids at Vati and Betty’s backyard wedding, at which I was rocking a questionable fashion choice.

With both sets of parents at my wedding.

With Vati and my older son

My younger son, looking a bit like a Flocki himself.